It was a big day for us. Even seventeen years later, I can still remember walking up the “Alice in Wonderland”-like corridor, with the pattern of its wooden walls oriented downwards as the floor sloped up, leading us to the stage. Our concert band was about eighty strong, with an unbalanced eight tuba players (three or four would have been more appropriate for a band this size), and I was one of them. We were taking part in the Singapore Youth Festival, a biennial competition for school bands, and were under significant pressure to play well, both because we had spent the last year practicing intensely, but also to live up to the collection of gold medals spanning the past ten years that hung on the wall of our band room.

We took our seats for a moment, but then stood all at once as our conductor walked up to the podium, our instruments gleaming under the stage lights – as a final ritual, we had spent the last night polishing them. He motioned for us to sit, and waved his baton for us to play a “Bb” note, checking our tuning one last time. A “cut”, a short pause, another wave, and we were off. The next fifteen minutes or so were a blur. I vaguely remember thinking we sounded good, although a cornet player missed a high “C” at the very end, souring the performance in our minds.

And just like that, the central point of hundreds of hours of practice vanished – it was time to put away our instruments and take our seats in the auditorium, awaiting our fate. I don’t remember any of the other bands that played that afternoon; we were far to self-absorbed to pay much attention. I remember being caught in between wanting them to announce the results immediately, but also wanting an appropriate amount of suspense before the tension was released. Two years later, with the benefit of experience, and as a better group of musicians, I wouldn’t feel as nervous – I remember walking off the stage fairly confident that we had nailed our performance.

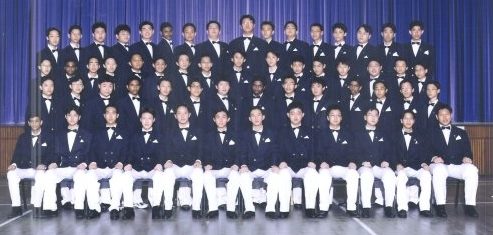

The fifteen minutes or so on stage were the culmination of more than a year of preparation. A few weeks prior, we all had to be fitted for blazers, and get haircuts to make sure we looked presentable on stage. I remember hearing the barber repeat, in broken English: “Don’t worry, I make it neat… neat”, as he buzzed off entire swathes of my friend’s shaggy mop. Another friend walked in the next day nearly bald, and was met with derisive laughter. As it turned out, the barber had asked him “What number?” – referring to the size of the clippers, and our friend, without having any idea what that meant, answered “2”, which is the standard for fresh recruits in the army.

In retrospect, the last year had been ridiculously intense for a group of 13 to 16 year old boys. Our regular schedule consisted of a mix of of full band practice, sectionals, and individual practice, four to five times a week (in the afternoons after school and on Saturdays), for two to three hours. However, in the last three months, we had supplemented that by coming to school at 6:30am to practice for an extra hour before school started, and by staying for a couple of hours past our usual practice time, wrapping up at about 7 to 8pm. During these months, our conductor, who was strict at the best of times, took on a “J.K. Simmons in Whiplash” quality – he once kicked a floor air-conditioning unit, only to arrive at the next practice hobbling, with a cane. We kept quiet about it, though.

To further prepare, we also had band camp. Unlike the “American Pie” variety, where apparently no practice takes place, ours basically consisted of practice from morning to night, in addition to foot drills (we were a “military” band), push-ups, and running (either to build lung capacity, or as punishment for being unruly or playing poorly). Once, we found ourselves running around the rugby field at midnight, doing push-ups whenever our drum major blew a whistle. These had to be done synchronously – a “timer” would yell “down”, and we would yell the count in return. I’ve long forgotten why we were doing this, but still retain the comical (in retrospect) memory of noticing a conspicuous silence from my right, only to realize that our “timer” had passed out, and was lying face down in the dirt.

Back in the auditorium, after the last band had played and shuffled to their seats, the results were announced. My stomach was in knots as I heard a bunch of silver and bronze medals being awarded, and I thought I would throw up as the announcer took their time in drawing out: “Saint Andrew’s School Military Band…Gold”.

To date, this is the only time where I can distinctly remember feeling the slightest out-of-body experience, jumping to my feet and cheering without consciously willing myself to do so.

I didn’t know it then, but that cycle of events, lasting just over a year, would have a profound impact on my life. It was the first time my 13-year-old self saw the point of preparing for a goal way out in the future (remember that a year was about 8% of my entire life at that point). I’m sure it was the same for many people in my year, too. What we learned, however, was deeper than just “working hard”. Instead, we formed a culture that many of us still try to live up to today, for better or worse. By being punished for someone else’s mistakes, we learned that nothing was “Somebody Else’s Problem”; under the constant reminder that our actions had consequences for the reputation of those who came before and after, leaving the band “in a better state than you found it” became like mantra. There are many of us who might have been put on different paths in life if not for this shared experience.

Of course, that sense of perfectionism and elitism came with a price, at least, for me personally – a general sense of constant self-loathing, an attitude of “do it well, or don’t do it at all”, and a strong preference for “my kind of people”.

For the longest time, while learning to play the guitar, I refused to play anything by my hero Stevie Ray Vaughn in front of anyone else, because I felt like I would be doing a disservice to the music. Even today, I can still feel in a gnawing in my stomach when I, or other musicians are “off”, and the back of my head is still filled with snarky quips that I would never say, like “This isn’t music, this is just noise”, or “Let’s try that again – this time, correctly.”

Outside of music, I spent many years ashamed of being less than perfect at anything. It took me a long time to realize the most simple, blatantly obvious thing: That before you’re good at something, you’re going to be bad at it. It also took me too long to realize that you don’t have to set out to finish everything you start – that some things don’t have a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and you only realize halfway; that there’s nothing wrong in giving up.

Despite the anxiety and despair that these flaws have occasionally caused, I wouldn’t trade them for the world, for they have afforded me a life I would not otherwise have had. Besides, it’s far easier to lower your standards when needed than to try to conjure them up after a lifetime of absence.